Our energy levels can be affected by so many things, but one of the fundamental areas to consider is that of impaired oxygen delivery or what might be more commonly associated with anaemia.

Anaemia is a condition where your blood is deficient in haemoglobin or red blood cells. Red blood cells help to carry oxygen from the lungs to the tissues of the body as well as carry carbon dioxide from the tissues to the lungs where the carbon dioxide is then exhaled.

The classic symptoms of anaemia include:

- Tiredness and fatigue, especially on exertion

- Pale looking skin

- Feeling weak

- Shortness of breath

- Reduced concentration

Other symptoms may also include:

- Coldness in the hands and feet

- Rapid heart rate

- Dizzy spells

- Getting easily irritated

- Cramps

We don’t have to experience all these to have anaemia, in fact you may only experience one or a few of these symptoms, in particular some of the classic symptoms listed above. You also don’t have to have full blown anaemia for it to be contributing to more mild symptoms, as a result, the potentially for impaired oxygen delivery is sometimes missed when one has milder symptoms and borderline blood test results.

What causes Anaemia?

There are three broad reasons why you may experience anaemia, but these three reasons also open it up to numerous underlying causes.

- Anaemia caused by blood loss (loss).

- Anaemia caused by poor production of red blood cells or haemoglobin (production).

- Anaemia as a result of excessive red blood cell destruction (destruction).

Anaemia due to blood loss is often going to result from an acute incident (accident/injury etc) or can also be related to a chronic issue such as slow bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract, perhaps because of a peptic ulcer, inflammatory bowel issues, haemorrhoids, heavy menstruation etc. Anaemia must be taken seriously. If it is noted through symptoms and then confirmed with blood testing, a wider understanding of the health of that individual is critical and, in some cases, further investigation by a gastroenterologist or endocrinologist etc may be warranted to rule out other conditions or diseases.

Excessive red blood cell destruction can result from the production of low quality/defective haemoglobin, such as sickle cell anaemia, certain nutrient deficiencies, hereditary enzyme defects etc. Again, this is something that should be investigated further and diagnosed by a qualified medical professional.

Anaemia due to production issues is by far and away the most common cause of anaemia, however you must rule out destruction and loss reasons, otherwise you may be ignoring a red flag that could indicate something more sinister or a true underlying factor that must be taken into consideration.

When it comes to production there are numerous influencing factors, in particular from a nutritional perspective. Later in this article I provide a table to help you interpret a blood chemistry from a more holistic and optimal health perspective.

Some of the factors that lead to anaemia, because of their effect on the production of haemoglobin and red blood cell production include:

- Nutritional factors – issues with low levels of Iron, B12, Folate, Copper, B6, Vitamin C, Vitamin A, Zinc, B1 protein, arginine and excess alcohol

- Hormones – Low levels of Testosterone or Thyroid hormones

- Kidney dysfunction

- Inflammation & Oxidative Stress

Assumptions are often made that anaemia is the result of an iron deficiency and so often when you try to look into the cause of anaemia, all you will find is conversation about iron deficiency. The reality is iron is just one of many factors and in fact may do a lot more harm than good if supplementing with it when it is not required.

Why does anaemia cause low energy?

Anaemia causes low energy plus a whole bunch of other symptoms because the red blood cells and haemoglobin help to deliver oxygen to our cells. Haemoglobin is the oxygen carrying molecule in red blood cells.

Oxygen is fundamental for the cells of our body to make energy and enable our cells to do what they need to do, no matter what that cell is. If we cannot make energy efficiently within our cells we then start to experience the symptoms of anaemia.

The food you eat must go through numerous processes to be turned into usable energy. Not just from a digestion and absorption perspective, but once it is within our cells and more specifically the mitochondria of the cell. Therefore, just because you have eaten something does not mean you will make energy out of it.

Anaemia results in impairing one of the fundamental systems in the body that helps us turn food into energy. Anaemia however is in and of itself a symptom and not a disease, and this is where you then have to look at destruction, loss or production as the underlying issue.

Complete Blood Count Testing and Anaemia

Running appropriate lab tests is crucial in helping to determine if you have anaemia, but also provides significant clues as to the underlying cause of the anaemia as well.

A standard Complete Blood Count (CBC) will typically look at the following:

- Red Blood Cells (RBC)

- Haemoglobin (Hb)

- Haematocrit (Hct)

- Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV)

- Mean corpuscular Haemoglobin (MCH)

- Mean Corpuscular Haemoglobin Concentration (MCHC)

- Red Cell Distribution Width (RDW)

- Platelet Count

- Mean Platelet Volume (MPV)

- White Blood Cells and typically with differentials (neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, basophils, eosinophils)

Just these markers alone can tell you so much about one’s physiology when read correctly. The reason for this is because when one understands biochemistry and physiology, one starts to understand the nutrients involved in the production of haemoglobin and the health of red blood cells.

Other markers can also be exceptionally useful and are not unusual or rare tests to run, these include:

- Iron

- Ferritin

- Total Iron Binding Capacity (TIBC)

- Transferrin Saturation

- Homocysteine

- Ceruloplasmin and/or serum copper

- Reticulocyte Count

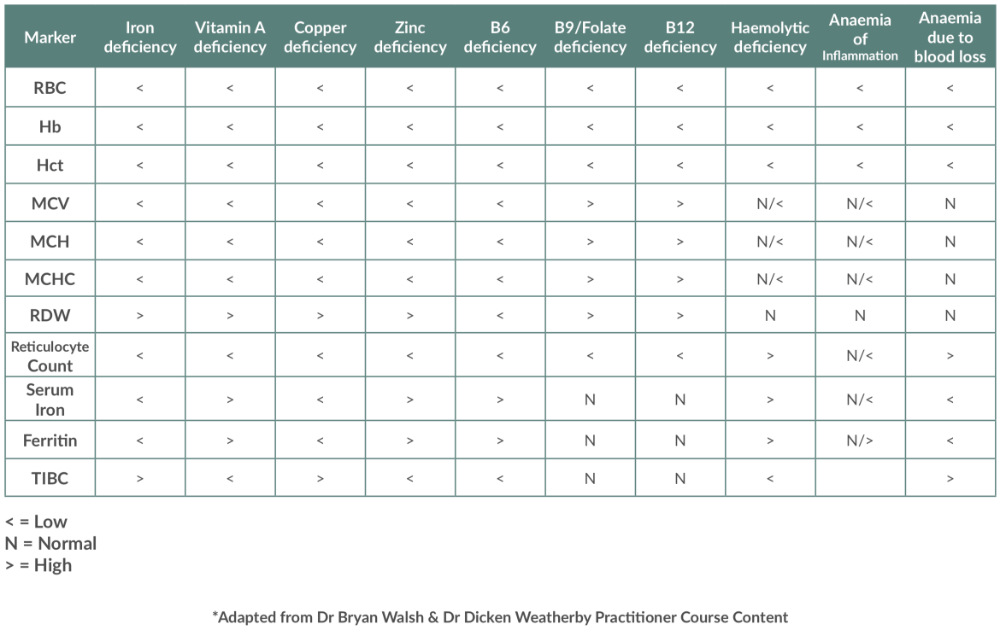

Anaemia patterns and what they mean

Observing the MCV, MCH and MCHC can help highlight three particular types of anaemia associated to low haemoglobin and the size of the red blood cell.

- Macrocytic anaemia

- Normocytic anaemia

- Microcytic anaemia

Macrocytic anaemia (when the red blood cells become large and anaemia is present) will be concluded when MCV, MCH and MCHC are elevated. This may result from B12/folate issues, vitamin C deficiency, alcoholism, vitamin B1 deficiency, with the most common of these being B12/folate levels.

Normocytic anaemia (when red blood cells are normal size and anaemia is present) will be concluded when MCV, MCH and MCHC are normal. This may result from excessive breakdown of red blood cells, inflammation, magnesium deficiency, selenium deficiency, oxidative stress, vitamin C deficiency, kidney dysfunction or low EPO production.

Microcytic anaemia (when red blood cells are small and anaemia is present) will be concluded when MCV, MCH and MCHC are low. This may result from iron deficiency, copper deficiency, vitamin B6 deficiency, zinc deficiency, vitamin A deficiency and vitamin C deficiency.

To help you find some of the main potential underlying cause of your own anaemia, I have created a table that you can refer to.

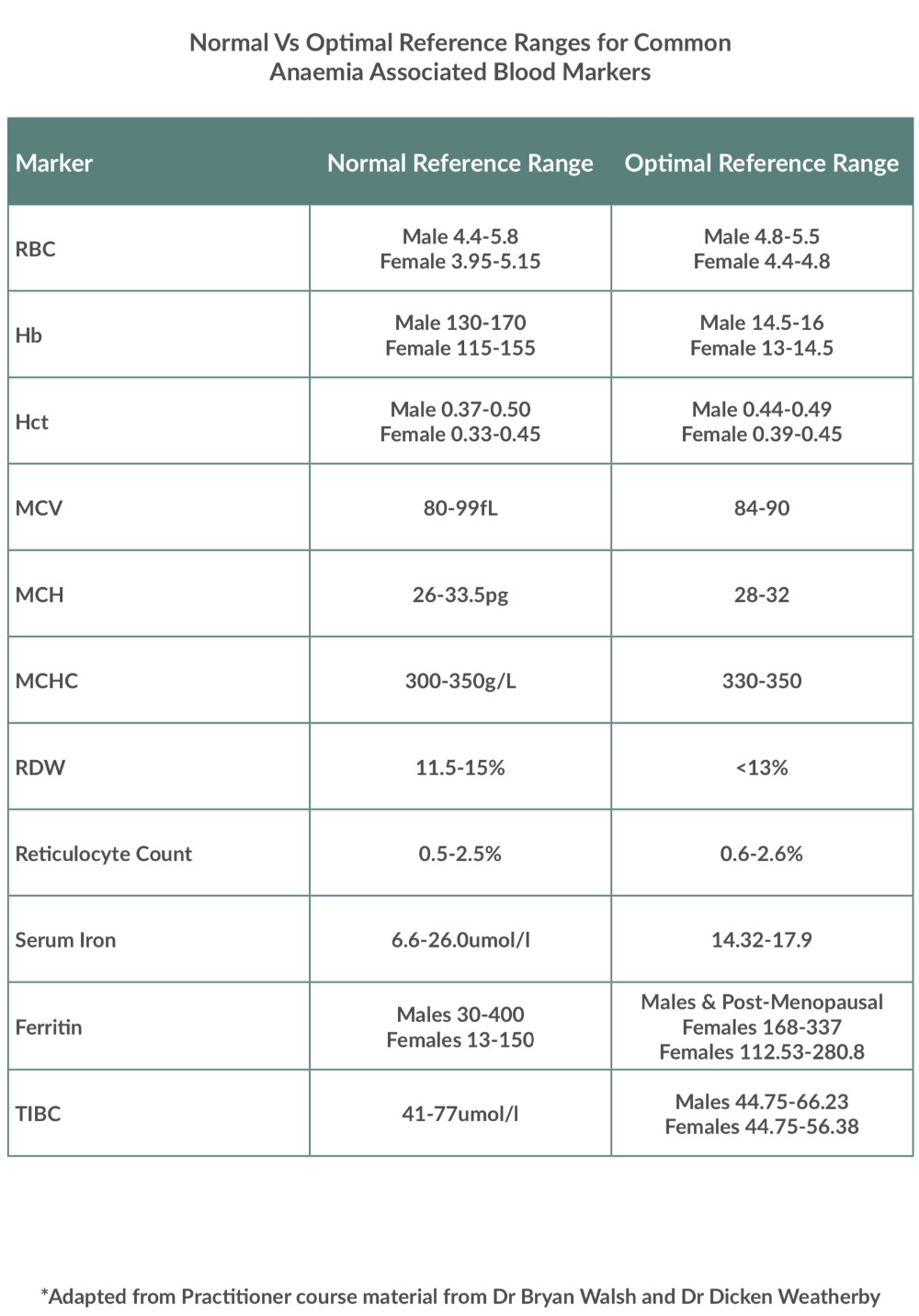

Normal vs Optimal Reference Ranges on a Complete Blood Count

One of the considerations we also have to look at when it comes to assessing blood tests is that of normal reference ranges vs optimal reference ranges.

Reference ranges are seen as the most clinically important aspect of interpretation. Normal reference ranges are typically set based upon the normal being 95% of the population, thus the top and bottom 2.5% are seen as being out of the normal reference range.

Unfortunately, there can be issues with normal reference ranges and how they are achieved. Sometimes normal reference ranges are concluded from research, but a lot of the time they are created based upon the normal levels of a given population of people. Different labs will often have their own reference ranges that differ slightly, but often data is based upon the norms of, shall we say sick populations of people rather than taking the most healthy people and testing their blood to see what the “normal” levels are.

There has been a movement in the more functional medicine and nutritional field to incorporate reference ranges based upon optimal values as well. This can sometimes be set by simply reducing the standard deviation, essentially squeezing the reference range; however, my preference is the use of scientific data that is out there outlining optimal levels, perhaps based on outcomes such as all-cause mortality.

All of this aside, I have produced a further table with the primary anaemia related markers, outlining typically normal reference ranges and what are seen as more optimal reference ranges.

Normal Vs Optimal ranges for common Anaemia

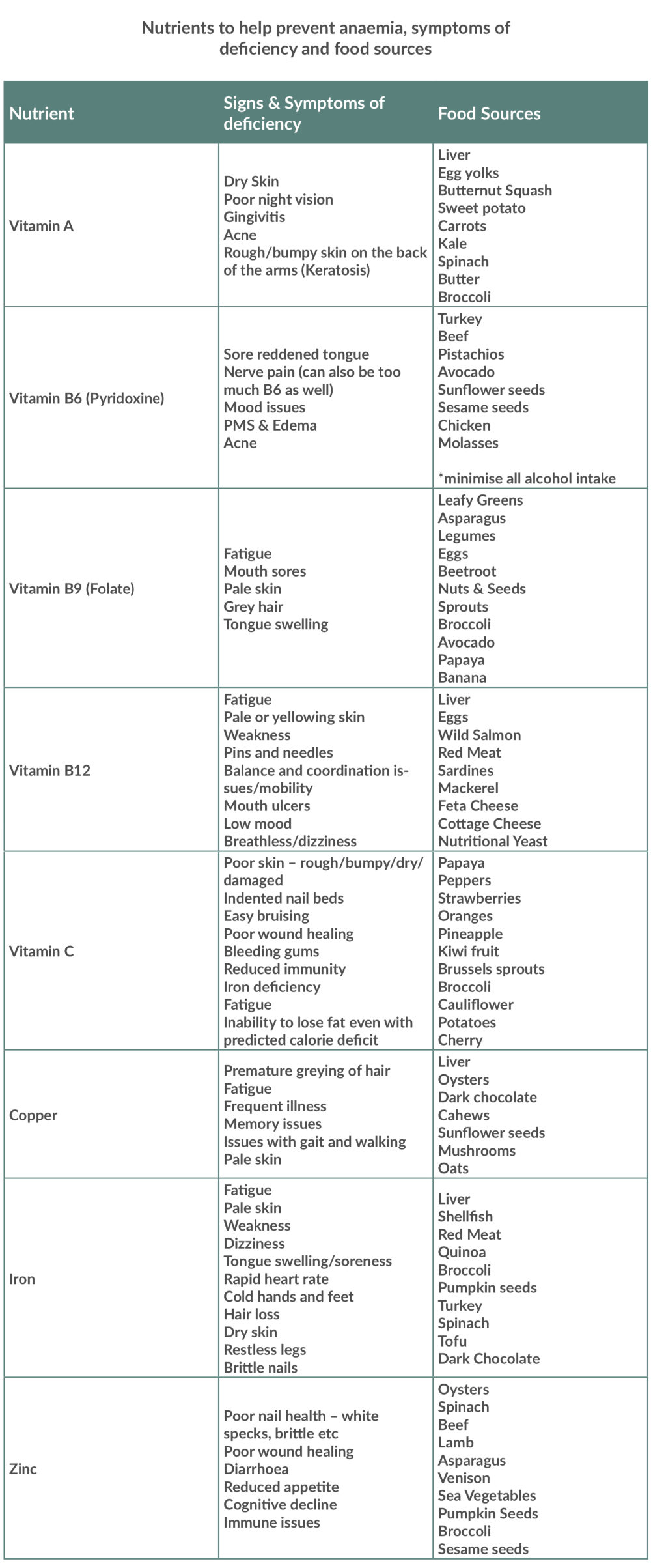

Nutrients and the foods that may help reverse or prevent anaemia

The next thing you might be wondering is, are there any signs and symptoms of nutrient insufficiencies related to the nutrients that help to prevent anaemia from developing and if so what foods might be good for me to introduce into my diet as a way of helping to prevent anaemia and perhaps as part of your treatment process if anaemia is present and you are aware of the underlying nutritional cause.

Below is another table that you can utilise to help with this.

Nutrients to help prevent Anaemia

Conclusion

If you are suffering with some of the mentioned symptoms within this article, then you should consult with your GP to discuss them and look at running some blood tests. The blood tests I have spoken about are easily available both with your GP and also privately at very low cost.

The next step is taking those results and putting them in context with your goals, nutrition, lifestyle, personal circumstances etc. This is where myself or one of the practitioners that I work closely with will be able to help. We can help you adapt your diet, modify your lifestyle, support the behaviour change and where necessary provide support for further investigations, particularly if you find yourself frustrated with the progress you have been making so far with your healthcare professional.

Contact Steve Grant Health

To learn more out how Steve Grant Health can assist you on your journey, please fill out the enquiry form below.

Please note that depending on your specific circumstances and goals, Steve may recommend that you work with one of the specialist practitioners within his network of trusted professionals.

If you have been referred by a clinician, please complete the form and ensure that you state who has referred you or have your practitioner email Steve direct to make a referral that way.

Click the button below to open the client enquiry form:

[widgetkit id=”643″]